BERTology [research review]

The primary goal of this post is to summarize several recent papers exploring what BERT, a contextualized word embedding model, can and can’t do. If you’re new to word embeddings in general, my other post has more background.

Introduction: Contextualized word embeddings

One of the major limitations to embedding approaches such as word2vec and GloVe is that they don’t distinguish between different senses of a word. That is, the word “bank” would map onto the same, static vector in both sentences below:

I went swimming along the bank.

I deposited my check at the bank.

This is obviously not optimal. “Bank” is an example of a homophone––the same word form has multiple, unrelated meanings, and the word embedding should reflect those different meanings in the appropriate context.

Homophones are a stark illustration of why using a single word embedding for a given wordform (like “bank”) is problematic. But the problem isn’t unique to homophones. Arguably every word means something different in different contexts. As Jeff Elman pointed out (Elman, 2004), words are cues to meaning; the nature of that meaning will depend on exactly what was said before. For example, the verb “run” conveys something slightly different in the following sentences:

1) The jaguar runs.

2) The child runs.

3) The clock runs.

Both (1)-(2) connote that some animate entity is moving through physical space, and also imply something about the speed of their motor routine. But our mental representation of a jaguar running is likely quite different from our representation of a child running. And (3) appears to be a metaphorical usage of the verb “run”. All three uses share something in common, but they’re also somewhat different––and our representation of “meaning-space” ought to capture that.

This is exactly the problem that contextualized word embeddings aim to solve. Rather than mapping a wordform onto a single, static vector, contextualized approaches produce different vectors in different contexts. Notable recent approaches include ELMo (Peters et al, 2018), XLNet (Yang et al, 2019), and of course, BERT (Devlin et al, 2018). The goal of this post isn’t to describe the BERT algorithm; there are plenty of blog posts doing that already (see here, here, and here for a start).

Rather, my goal is to summarize some recent papers in the trending subfield sometimes called BERTology: the study of the inner workings of BERT.

BERTology: investigations of a neural network

Why is investigating the inner workings of BERT interesting or useful?

The reason that’s usually cited is that many modern language models are thought to be black boxes. This is something of a catch-all term used for much of contemporary machine learning models, which basically means something like: “It works pretty well, but we have no idea how”1. BERTology aims to address this problem by determining what sorts of information BERT picks up on, and where in the network it seems most sensitive to that information––in other words, making the network more transparent.

Transparency, in turn, is important for all sorts of other things. First, if the goal is to use BERT (or really any machine learning model) in an applied setting, my personal opinion is that it’s important to have an idea of how it works, at least for the task in which it’s being applied. Otherwise, these models might be encoding all sorts of biases and spurious correlations, which impairs their performance in a real-world setting and at worst, can perpetuate systemic biases in society (as Cathy O’Neil demonstrates in detail in Weapons of Math Destruction (O’Neil, 2016)). Second, a better understanding of how BERT and other models learn to encode information from language can help advance research in Linguistics and Cognitive Science. There’s a long history of using computational models to better understand human cognition (Futrell et al, 2019), and while BERT’s algorithm isn’t that similar to how humans process language, it’s still a useful reference point. BERT learns only from textual input (though a massive amount of it); this allows us to ask about what sorts of things can be learned purely from linguistic input alone, and what sorts of things might require physical experience in the world, social interaction, and more.

So what does BERT “know”, and how can we know? This question is usually operationalized in the form of using BERT embeddings on some downstream task (e.g., semantic role labeling). If a model equipped with BERT embeddings is successful, it implies that the BERT embeddings have encoded the information required to complete the task. From this, researchers often infer that BERT “knows” or somehow encodes the broader class of information that task is meant to reflect––not unlike how psychologists study cognitive abilities like Theory of Mind using a variety of different tasks, each of which is meant to somehow reflect the underlying ability. In other words, these tasks are operationalizations of some underlying theoretical construct. Importantly, the inference from “successful performance on Task X” to “understands Domain Y” is not always warranted in Psychology, and as we’ll see below, it’s also not always warranted in BERTology.

What does BERT know about word senses?

Given that a major goal of BERT is to distinguish between different senses of a word, a logical question is to ask how BERT performs on word-sense disambiguation: the task of predicting or classifying the intended sense s of some word w in some context c (where w usually has >1 sense). This amounts to something like P(s|w, c) for each possible sense of w.

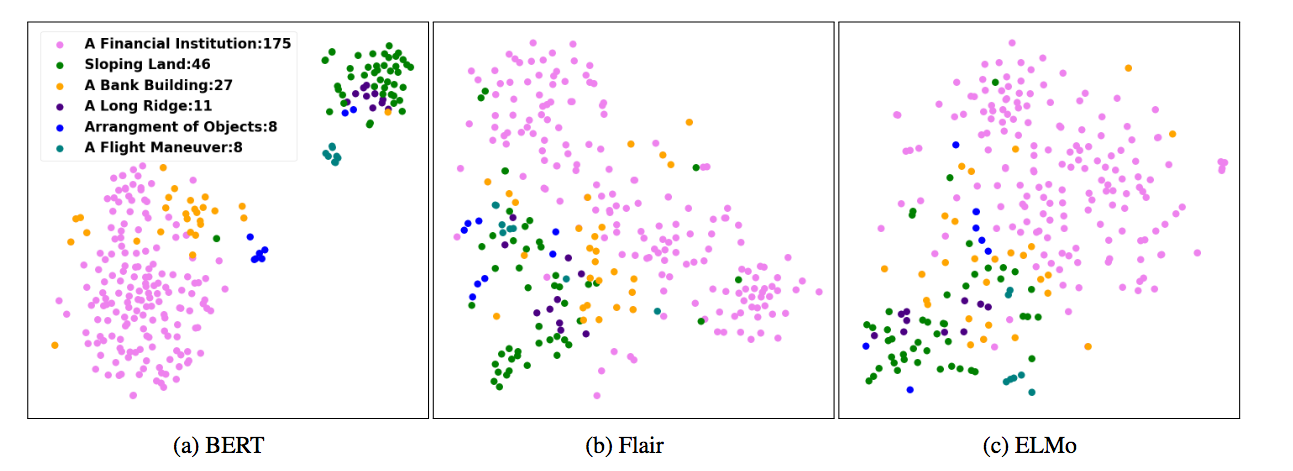

The answer largely seems to be yes: BERT embeddings appear to provide sufficient information to predict the intended sense of a word (Wiedemann et al, 2019). On multiple datasets, BERT emerges as the best language model, handily beating out previous embedding models. Distinct senses of a word formed identifiable “sense clusters” in meaning-space (see the figure below for an example using the word “bank”).

Notably, these sense-clusters were considerably more distinct for BERT than for FLAIR or ELMo, two other contextualized embedding models.

Of course, the work doesn’t end here. As I described earlier, homophony isn’t the only kind of lexical ambiguity. Even more pervasive than homphony is the phenomenon of polysemy: words with multiple, related meanings. Polysemy often occurs via metaphorical extensions of a word, e.g., “swallow (a pill)” is extended to “swallow (an argument)”, but there are many other mechanisms identified by linguists (e.g., metonymy, narrowing, etc.). Personally, I think a fascinating line of research would be to ask whether these kinds of polysemous relationships correspond in systematic ways to transformations in BERT-space.

Tenney et al (2019): using “edge probes” to learn what BERT knows, and where

BERT embeddings can be used for much more than just word sense disambiguation. This recent paper by Tenney et al (2019) uses the technique of “edge probing” to figure out exactly what information BERT knows, and where in the network this information seems to be represented or enacted.

I believe the notion of an “edge probe” actually comes from Neuroscience (though I could be totally wrong about this connection). Early work on the visual system (Hubel & Wiesel, 1959) found that certain cells in area V1, also known as the primary visual cortex, responded selectively to lines of different orientation. That is, one cell might respond selectively to vertical lines, another cell might respond selectively to horizontal lines, and other cells might respond to lines somewhere in between. A given neuron’s selectivity can be determined by examining its tuning curve; that is, by parametrically manipulating properties of a stimulus (e.g., its orientation) and looking at the firing rate of the neuron. This basic approach has been extended with great success, leading to the finding that neurons in different parts of the brain are selective for all sorts of different things––from an animal’s location in space to the frequency of acoustic input.

An analogous approach can be applied to artificial neural networks: present some sort of input to the network, and take a snapshot of the network’s “activity”. Depending on your question, you might be interested in the activity at a specific layer of that network (e.g., how many units are activated, or which ones), or even in the changes in activity as additional stimuli are presented. By manipulating properties of those stimuli, you can ask about various input dimensions correspond to various activation profiles in the artificial neural network.

This was the approach taken by Tenney et al (2019). Here, their question was how well BERT extracts different kinds of information about language, as measured by the performance of BERT embeddings on a number of different tasks (each intended to reflect a certain kind of linguistic knowledge). These tasks included, among other things: part of speech (POS), syntactic dependencies, named entities, and semantic role labeling (SRL). Further, the authors wanted to know where in BERT this information was most salient––e.g., whether part of speech information was accessible in the first layer, but semantic information required for SRL was only accessible in later layers.

Concretely, for each task, BERT was given some set of input tokens T, and in turn produced a set of layer activations H[L], where L is the number of layers. For a sentence like he smoked toronto in the playoffs..., and a 10-layer model, BERT would produce 10 sets of activations, corresponding to each successive layer. H[0] would correspond to the initial (non-contextual) layer, H[1] to the first contextual layer, and so on. These embeddings could then be used to train a classifier for each task. Critically, the authors manipulated which layers were used for training the classifier, allowing them to compare the performance of a classifier equipped only with H[0] to a classifier with H[1], H[2], and so on. They then measured the improvement to a classifier (differential score) as more layers were added to the model 2.

Interestingly, they found that basic syntactic information (such as part of speech) does appear to be accessible in earlier layers of the network, while high-level semantic information was only accessible higher layers. But syntactic and semantic information was also distinguished in terms of its localizability. That is, the predictability of syntactic information could be localized to specific units in specific layers, while semantic information could not––it was more distributed. In a way, this pipeline recapitulates traditional approaches to Natural Language Processing and even psycholinguistics, hence the title of the paper: “BERT Rediscovers the Classical NLP Pipeline”.

Commonsense: what does BERT know about the world?

The papers described above demonstrated that BERT knows a decent amount about language. But how much does this knowledge translate to general knowledge about the world? This is sometimes called commonsense knowledge; the idea is that there are certain facts about the world, or ways of reasoning about the world, that humans learn and do effortlessly, but which are quite hard to teach to a machine. For instance, how do we learn the properties of objects (“boats require fuel”), as well as their affordances (“boats can be driven”). There’s a long history of Artificial Intelligence researchers attempting to build in this “commmonsense” knowledge into their systems, traditionally using hand-coded approaches; these approaches work well in small, restricted domains, but are very challenging to scale up. Thus, one tantalizing question is whether BERT and other language models can be used to rapidly scale systems for general-purpose, commonsense reasoning.

Properties and affordances

This is the question asked by Forbes et al (2019). Specifically, the authors asked whether contextualized representations of word meaning could improve a model’s performance on tasks involving identifying object properties (static characteristics of objects, e.g., edible or stationary) and affordances (what actions that humans can do with an object, e.g., wear or take off). In English, these features roughly correspond to adjectives and verbs, respectively. The properties of an object are clearly related to its affordances, and can even be inferred from sentences that make those affordances clear; for instance, the sentence “She looked through the keyhole” activates the affordance look-through(x), which implies transparent(x).

How well can BERT learn these relationships? For example, given an object boot, and knowing its affordances wear and kick off, how well can we predict its properties?

These three dimensions––objects, properties, and affordances––form three edges of a graph. The task is thus to learn to predict:

1) The properties of a new object, e.g., O --> P.

2) The affordances of a new object, e.g., O --> A.

3) The properties compatible with an affordance, e.g., A --> P.

These relationships are learned and tested from two different datasets: the abstract dataset (a compilation of object-property pairs), and the situated dataset (a compilation of objects, properties, and affordances, taken from situated photographs). They then consider the performance several different word embedding models––two static embedding models, and two contextualized representations (ELMo and BERT).

Overall, they find that all the models perform the best on the abstract dataset, in which properties must be inferred from objects (O --> P). The models are worse at this same task (O --> P) when trained on the situated dataset, though the numbers are considerably higher when inferring affordances from objects (O --> A), also on the situated dataset. By far the worst performance is the final task: inferring properties from affordances (A --> P). In most of these cases, BERT performs the best.

The finding that all models have a hard time relating properties to affordances is particularly interesting, given that (as the authors note) these features are likely not mentioned together very often; “their mutual connotation naturally renders joint expression redundant” (pg. 6). This raises the question: what information do humans use to learn these kind of relationships? As the authors point out, an obvious answer lies in the theory of embodied cognition: “the nature of human cognition depends strongly on the stimuli granted by physical experience” (pg. 6). Of course, these results do not prove that learning property/affordance relationships is impossible from linguistic input alone––it’s possible the task could be adjusted, for example, or that BERT could be improved upon further to better extract and connect these features. But human agreement is more than double BERT’s performance on the same task, indicating that humans share some kind of mutual understanding of the objects in this task that BERT does not, potentially derived from our physical experience with those objects.

Moving forward, then, the question becomes: how much experience in the physical or social world is required to successfully learn these relationships? Which abstractions are permissible, and which are not? How much of this information needs to be engineered explicitly in a top-down way into a language model, and how much can be learned on the basis of regularities in the input?

Argumentation mining: BERT’s “clever Hans” moment

Another challenge related to commonsense knowledge is argumentation mining: extracting components of an argument from text, then determining which pieces of text correspond to claims, and which correspond to supporting or opposing evidnece for those claims.

Research often focuses on the latter problem in the form of warrant identification, which can be operationalized as follows. Given some claim C and a reason R, a model must learn to identify which of two possible warrants {w1, w2} actaully supports that claim by way of R. Consider the following example, taken from Niven & Kao (2019):

Claim: Google is not a harmful monopoly.

Reason: People can choose not to use Google.

Warrant 1 (w1): Other search engines don't redirect to Google.

Warrant 2 (w2): All other search engines redirect to Google.

The task is then: which of {w1, w2} supports the claim? A human would likely reason as such: if “people being able to choose not to use Google” implies that “Google is not a harmful monopoly”, then w1 is a better piece of evidence for that claim than w2. In contrast, w2 supports the opposite of the claim. That is, R ^ w1 --> C, and R ^ w2 --> ~C.

This is called the Argument Reasoning Comprehension Task (ARCT), and is known to be incredibly challenging for machines, since it appears to require general world knowledge. To solve the problem above, you probably need to know that Google is a search engine, what a “monopoly” is, and how web re-directs relate to the concept of consumer choice and monpolies (Niven & Kao, 2019).

Hence the authors’ surprise when BERT achieved a remarkable performance of 77% test-set accuracy on this task. That is, a classifier trained with BERT sentence embeddings was able to choose the correct warrant to support some claim 77% of the time. Given this result, the authors ask: what do BERT embeddings capture about argument structure that allows them to solve this task?

The answer manages to be disappointing, interesting, or vindicating, depending on one’s perspective. Put simply, BERT embeddings don’t appear to capture anything “deep” about the structure of an argument, at least in terms of what’s required to the solve the task. Rather, they’re just very good at capturing statistical confounds in the data: lexical and syntactic cues that happen correlate with the intended answer. The authors write: “We demonstrate in this work that BERT’s surprising performance can be entirely accounted for in terms of exploiting spurious statistical cues” (pg. 2).

Specifically, the authors identify a few factors that reliably correlate with the correct answer across items. For example, the word “not” is more likely to appear in the correct warrant than the incorrect warrant (the distractor). Using only this binary cue––whether or not the warrant contains the word “not”––the authors achieve roughly 61% accuracy on the task, i.e. above chance performance. Several other spurious lexical cues further boost performance, such as “is”, “do”, and “are”, as well as bigrams occurring with “not”, such as “will not” and “cannot”. These are all examples of confounds: selecting the answer that contains the word “not” doesn’t mean that BERT has understood the argument, only that it’s identified a spurious cue that happens to correlate with the right answer 3.

To illustrate why this is problematic, consider inverting the argument above:

Claim: Google is a harmful monopoly.

Reason: People can't choose not to use Google.

Warrant 1 (w1): Other search engines don't redirect to Google.

Warrant 2 (w2): All other search engines redirect to Google.

Now the correct answer is w2, because it’s the piece of evidence that would be consistent with the claim that Google is a harmful monopoly. It’s pretty easy for humans to adjust to this change in the argument structure, because we have the background knowledge and also the understanding of how logical arguments are supposed to work. Now that the claim is inverted, the opposite piece of evidence (w2, not w1) is what supports that claim. To test this out, the authors developed an “adversarial” testing set by inverting all the claims in exactly this way. They trained a model on the original training set (with the spurious cues preserved), and then tested it on this adversarial set, and found that it achieved a mean of ~50% performance, i.e. random chance.

This is pretty convincing proof that BERT’s apparent success on the original task was due to exploiting these spurious cues. Remember: a human would be able to solve both the original and adversarial items with relative ease, or at least better than chance. But BERT’s failure to adjust to the change indicates that it was relying purely on the confounds.

As if this isn’t proof enough, the authors also found training and testing only on the original warrants (i.e. omitting the claims and reasons) still yields an accuracy of 71%. In other words, BERT could achieve better-than-chance performance without needing to understand the argument structure at all. If all you’re given is {w1, w2}, you shouldn’t be able to know which is the correct answer––either w1 or w2 could be correct, depending on the claim (as illustrated above).

Why it matters

BERT’s spurious success on this task is a matter of concern for the field. As noted above, these benchmark tasks are the main way by which we assess the quality of a language model. Each task is an operationalization of some deeper theoretical construct; that is, the ARCT task is a kind of stand-in for the broader category of argumentation mining, which in turn is a way to assess commonsense reasoning and world knowledge. As we saw, the design of the ARCT task suffered from a fundamental problem: it could be solved using spurious lexical cues. This means that the original ARCT task doesn’t accurately reflect the utility of a language model in solving the problem of argumentation mining––and if it rely on it to do so, we’ll overestimate the quality of our models.

This problem isn’t unique to NLP. There are many examples in Psychology of misattributing intelligent behavior to an entity because the researcher failed to eliminate a statistical confound. Most famously, clever Hans was a horse thought to be capable of doing arithmetic––until psychologist Oskar Pfungst discovered the horse was simply picking up on involuntary cues produced by his trainer (who, of course, could do arithmetic).

Even more broadly: all scientific practice relies on the use of some measurement to draw inferences about the phenomenon under investigation. This measurement is always an operationalization of a theoretical construct. Thus, it’s imperative to ensure that this operationalization is sensible, and that potential confounds are eliminated.

The Takeaway

The goal of this post was to provide a brief summary of recent work in BERTology. It’s by no means exhaustive, and many of the specific results will likely be out of date within the next year.

That said, I hope some of the more general principles derived from these studies stick around. First, it’s possible to gain a deeper understanding of “black box” language models by using them in a battery of tasks, and lifting analytical techniques from Neuroscience to pick apart the mechanics of a network. Second, we need to constantly interrogate our metrics and eliminate confounds.

And finally, even the best language models have a long way to go in terms of general world knowledge, which raises the question: how can one get on the basis of linguistic input alone? Humans learn in a rich, multimodal environment, which they explore in the context of a variety of goals, ranging from the physiological (food, sleep, safety) to the social (friendship, status, love). And importantly, we don’t reinvent the wheel every generation: human knowledge is encoded in the form of cultural practices, including––but not limited to––language. How much of this multimodal, social, goal-directed context is necessary for something like understanding? The answer, of course, might be everything.

References

Coenen, A., Reif, E., Yuan, A., Kim, B., Pearce, A., Viégas, F., & Wattenberg, M. (2019). Visualizing and Measuring the Geometry of BERT. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.02715.

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2018). Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805.

Elman, J. L. (2004). An alternative view of the mental lexicon. Trends in cognitive sciences, 8(7), 301-306.

Forbes, M., Holtzman, A., & Choi, Y. (2019). Do Neural Language Representations Learn Physical Commonsense?. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.02899.

Futrell, R., Wilcox, E., Morita, T., Qian, P., Ballesteros, M., & Levy, R. (2019). Neural language models as psycholinguistic subjects: Representations of syntactic state. arXiv preprint arXiv:1903.03260.

Goldberg, Y. (2019). Assessing BERT’s Syntactic Abilities. arXiv preprint arXiv:1901.05287.

Hewitt, J., & Manning, C. D. (2019, June). A structural probe for finding syntax in word representations. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers) (pp. 4129-4138).

Hubel DH, Wiesel TN (1959) Receptive fields of single neurones in the cat’s striate cortex. J Physiol 148:574-591.

Kim, B., Wattenberg, M., Gilmer, J., Cai, C., Wexler, J., Viegas, F., & Sayres, R. (2017). Interpretability beyond feature attribution: Quantitative testing with concept activation vectors (tcav). arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.11279.

Niven, T., & Kao, H. Y. (2019). Probing neural network comprehension of natural language arguments. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.07355.

O’Neil, C. (2016). Weapons of math destruction: How big data increases inequality and threatens democracy. Broadway Books.

Peters, M. E., Neumann, M., Iyyer, M., Gardner, M., Clark, C., Lee, K., & Zettlemoyer, L. (2018). Deep contextualized word representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.05365.

Tenney, I., Das, D., & Pavlick, E. (2019). Bert rediscovers the classical nlp pipeline. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.05950.

Wiedemann, G., Remus, S., Chawla, A., & Biemann, C. (2019). Does BERT Make Any Sense? Interpretable Word Sense Disambiguation with Contextualized Embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.10430. [Link]

Yang, Z., Dai, Z., Yang, Y., Carbonell, J., Salakhutdinov, R., & Le, Q. V. (2019). XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.08237.

Footnotes

-

This is itself an interesting point, because from one perspective, we know exactly how these models learn––we know what data they’re exposed to, we know what their network architecture is, and we know how the algorithm is implemented. But “black box” means something a little deeper; it implies we don’t have mechanistic explanations of what a network “knows” (e.g., how it transforms and represents the input it receives). For instance, we know that a network is able to classify an image of a cat as CAT, and an image of a dog as DOG, but how? Similarly, a network might be able to semantic roles of a sentence, but how has it learned to do that? I won’t dwell on this point here, but the reason I find it interesting is that it raises fairly deep questions about what it means to understand an intelligent process. ↩

-

More information (more layers) should always improve the model, but the question is by how much. ↩

-

Skeptical readers might be thinking: how do we know this isn’t what humans do, too? Why do we assume that humans “understand” and BERT doesn’t? What is learning but the identification of associated cues? And you’d be exactly right in voicing this concern, which is exactly why the point of designing a research experiment is to eliminate all possible confounds other than the specific thing one is interested in. If you want to infer that

A --> B, you need to manipulateAand nothing else, and ask whether the manipulation ofAcorresponds reliably to differences inB. That’s what makes experiment design hard––the elimination of alternative explanations for a particular outcome. ↩