Effing the ineffable [research review]

“What’s that smell?”

Olfaction is a important sense: it’s largely what allows us to identify rotten food, it’s a huge part of our experience of flavor, and it may be deeply connected to emotions and memory.

Yet for the most part, people in Western, industrialized societies don’t appear to be very good at naming odors. Majid & Burenhult (2014, pg. 266-267) write:

Presented with familiar everyday objects, such as coffee, peanut butter or chocolate, ordinary people correctly name only around 50% of odors…If people displayed similar performance with a visual object, they would be diagnosed as aphasic and sent for medical help.

This might be because we simply don’t have that many words for odors. In particular, languages spoken by individuals in Western societies tend to have few, if any, abstract odor categories. When we refer to a smell, we typically do so by naming either its intensity (a pungent scent), its valence (a fragrant scent), or the source itself (cinnnamon). The first two strategies reflect a kind of abstraction, but this abstraction is more evaluative than qualitative—that is, we’re not necessarily referring to the kind of smell, but the kind of experience we associate with that smell. And the third strategy relies on referring to the specific source responsible for the odor percept.

The limitations of our olfactory language are quite clear when contrasted with visual domains such as color. English speakers have recourse to a variety of “basic” color terms (Berlin & Kay, 1991), including: red, orange, blue, yellow, and more. While these terms may have originated from words for real-world entities, they now reflect relatively abstracted categories: lots of things can be red, from firetrucks to roses. Even a swatch of color on a page can be red. (Of course, some shades are more prototypical members of a color category than others, but this merely reflects the fact that the category system has carved up an underlying physical space, with some instances being more “central” in a category than others.)

As Berlin & Kay (1991) describe, languages vary in the number of color terms they have, but for the most part, languages possess at least several abstracted, basic color terms. Yet this doesn’t appear to be the case for odor. Why not?

Differential ineffability of the senses

Because of our difficulty in referring to odors, the sense of smell is sometimes thought to be ineffable, i.e., difficult to put into words (Levinson & Majid, 2014). One way ineffability is measured or characterized is via codability: how easy is it for speakers of a language to express some percept/concept (e.g., an odor or color), and to what extent does the expression they choose align with the expressions that other speakers choose?

People in Western, industrialized societies exhibit notoriously poor codability for odor (Majid & Burenult, 2014), but not for other senses like color. This has led some to assume that maybe humans are just incapable of developing and using abstract words for smell. Olfactory specialist Hans Henning writes:

Olfactory abstraction is impossible. We can easily abstract the common shared color – i.e., white – of jasmine, lily-of-the-valley, camphor and milk, but no man can similarly abstract a common odor by attending to what they have in common and setting aside their differences. (Henning, 1916, p. 66)

If this is true—i.e., if humans really can’t develop abstract linguisitc categories for odor—then it’s likely due to constraints imposed by the underlying neural architecture for olfaction. The job of scientists would then be to figure exactly what those constraints are and where they come from.

But there’s a problem with the chain of inferencing described above. Much of the evidence comes from research on native speakers or English or other Western languages. Yet we already know speakers of these languages tend to be from WEIRD cultures: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. And WEIRD humans may not be representative of humans in general.

Majid & Burenhult (2014) put it better than I could (emphasis mine):

There are around 6000–7000 languages spoken today, each one a solution to the communicative situation faced by speakers in different socio-cultural and ecological niches. This raises the question of whether the apparent ineffability, or inability to put words to smells, is really telling us something about all of humanity, or something specific about speakers of English.

And in fact, there is considerable evidence that other languages, particularly those spoken by small, hunter-gatherer communities, do contain abstract words for smell. The Jahai people are on such group.

Olfactory codability across languages

The Jahai people are a group of nomadic hunter-gatherers, who live in the rainforests between Malaysia and Thailand. Critically, they appear to have “basic” smell words—over a dozen verbs of olfaction that are used to describe a wide array of odors. For example, the term CNes is used for the smell of “petrol, smoke, bat droppings and bat caves, some species of millipede, root of wild ginger, leaf of gingerwort, wood of wild mango”, and more (Majid & Burenhult, 2014, pg. 267).

Clearly, the Jahai olfactory lexicon is more expressive than the English lexicon. But does that translate into increased codability? That is, how easily do Jahai speakers name odors, and to what extent is there agreement across Jahai speakers about the label for a given odor? This is exactly the question that Majid & Burenhult (2014) address.

Design

The experimental design is relatively simple. 10 native speakers of Jahai were administered the Brief Smell Identification Test (B-SIT); 10 American English speakers, matched for age, were also given the test. In the test, participants are presented with a series of encapsulated odors, which are released by scratching a card with a pencil—similar to the “scratch and sniff” books you might’ve read as a child. 12 odorants were presented in total.

In addition to the odor test, participants were presented with a classic color naming test, to act as a within-language comparison.

Analysis

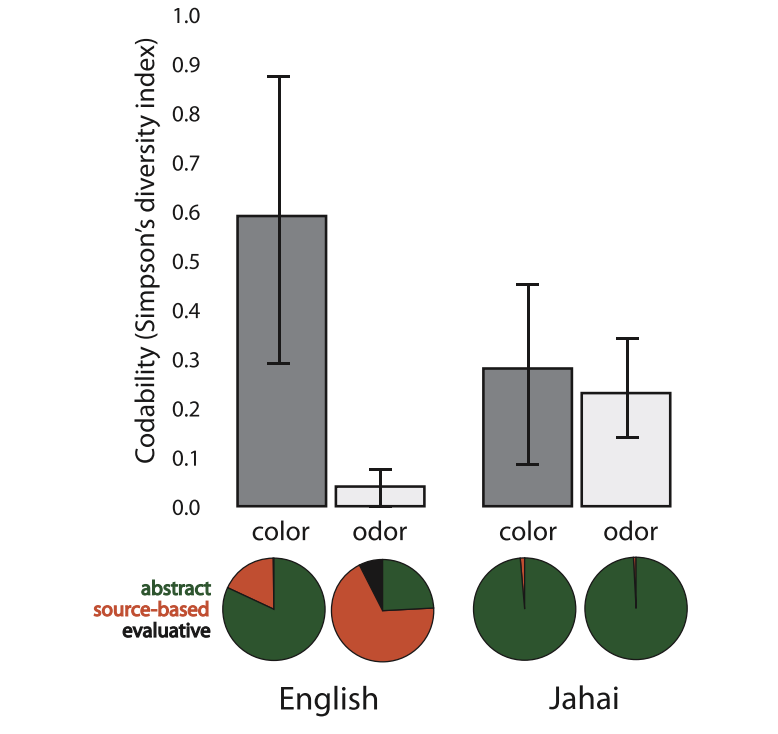

Codability was calculated using a measure called Simpson’s Diversity Index, or D. I won’t describe it in detail here, but the short version is that it measures the rate of agreement for a given odor by comparing the number of responses (i.e., from all the participants) sharing the same label to the total number of responses overall. A value of 1 thus indicates perfect agreement, while a value of 0 indicates that every participant used a different label.

Additionally, the researchers coded each response to determine the reference strategy used. Was it abstract (e.g., blue), source-based (e.g., cinnamon or banana-colored), or evaluative (e.g., nice or disgusting)?

Results

The primary results are depicted in a figure below (taken from Majid & Burenhult, 2014), and are (in my opinion) quite striking:

On the left, we see that English speakers exhibit much higher codability for color (~.6) than odor (~.1). This is to be expected, and reassures us that past results can replicate. Below the bar graph, we also see that English speakers rely primarily on abstract strategies to refer to colors, and source-based strategies to refer to odors. Again, this is consistent with past work.

On the right, we see that Jahai speakers don’t vary much in average codability for color (~.3) and odor (~.25). They also used abstract categories for all the items they were presented with, regardless of modality.

And critically: Jahai speakers exhibit much higher codability for odor than English speakers. So while codability of color is lower in Jahai than English, codability of odor is higher.

Takeaway

The results of Majid & Burenhult (2014) are inconsistent with the claim that humans simply can’t form abstract linguistic categories for odor. The Jahai people do it, and exhibit much higher inter-rater agreement on odor naming than English speakers. Furthermore, recent evidence (Majid et al, 2018) shows that Jahai speakers don’t just agree more on odor labels—they’re much, much faster at producing those labels.

There’s an important lesson in here about scientific generalization: if we want to make claims about all humans, then we need to draw random samples that are truly representative of all humans. And this isn’t just important for documenting cross-cultural variability: the data from the Jahai people appear to rule out the hypothesis that our lack of odor words is due to some innate fact of humans—it’s likely a product of cultural differences.

This, of course, raises the question: which cultural differences? One intuitive explanation is that hunter-gatherer groups, including the Jahai, simply need to communicate about different kinds of odors more frequently than humans in WEIRD societies, and thus, “hunter-gatherer olfaction is special” (Majid & Kruspe, 2018). Interestingly, however, recent evidence also suggests that it’s not just small hunter-gatherer groups with rich olfactory lexica: the Thai language, spoken natively by over 20 million people, appears to have a variety of abstract odor words as well.

In fact, there are certain specialized groups in Western countries that have well-developed olfactory vocabularies—wine experts, coffee afficionados, and more. Recent work (Croijmans & Majid, 2016) has found that domain expertise can boost codability: wine experts agreed more on the labels they gave for different wine odors than did non-experts (though expertise in coffee did not translate into increased codability about coffee odors). However, the effects of expertise are still relatively constrained to a particular domain: wine experts weren’t better than non-experts at naming everyday odors.

There are many questions that remain. Personally, one thing I find particularly intriguing is the question of whether English speakers—despite their poor agreement on odor labels—still tend to refer to relatively similar sources when describing odors. That is, two English speakers may not agree on the source they refer to (coffee vs. chocolate), but perhaps those sources are still more similar than one would expect if they were simply naming randomly—i.e., perhaps there’s an underlying similarity in their molecular structure, or in the distributional profile of those words. Another question relates to the work on wine expertise: even though wine experts didn’t show an advantage in non-wine domains, can they still learn non-wine labels better than a non-expert? How quickly can English speakers learn Jahai labels in general, and which individual differences predict variability in learning time?

References

Berlin, B., & Kay, P. (1991). Basic color terms: Their universality and evolution. Univ of California Press.

Croijmans, I., & Majid, A. (2016). Not all flavor expertise is equal: The language of wine and coffee experts. PLoS One, 11(6).

Majid, A., & Burenhult, N. (2014). Odors are expressible in language, as long as you speak the right language. Cognition, 130(2), 266-270.

Majid, A., Burenhult, N., Stensmyr, M., De Valk, J., & Hansson, B. S. (2018). Olfactory language and abstraction across cultures. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 373(1752), 20170139.

Majid, A., & Kruspe, N. (2018). Hunter-gatherer olfaction is special. Current Biology, 28(3), 409-413.

Wnuk, E., Laophairoj, R., & Majid, A. (2020). Smell terms are not rara: A semantic investigation of odor vocabulary in Thai. Linguistics.