Mixed Effects Models

Goals of the lecture

- The independence assumption of linear regression.

- What about when data are non-independent?

- Introducing mixed effects models.

- Fixed vs. random effects.

- Adding random intercepts.

- Adding random slopes.

- Mixed models in practice with

lme4.- Model comparison: the logic of likelihood-ratio tests.

glmer: generalized linear mixed models.

- Best practices.

Load libraries

Part 1: Independence

The independence assumption; why it matters; examples of non-independence.

What is independence?

Independence means that each observation in your dataset is generated by a separate, unrelated causal process.

- When you flip a coin, each flip is independent of the others

- The outcome of flip #1 doesn’t influence flip #2

- No hidden factors connect multiple observations

- Each data point provides new information

Why does independence matter?

Standard statistical methods (t-tests, OLS regression, ANOVA) assume independence.

When this assumption is violated:

- Standard errors are underestimated

- Confidence intervals are too narrow

- p-values are too small (inflated Type I error)

- Your conclusions may be wrong!

The problem: Treating non-independent observations as independent makes you overconfident in your results.

Example: Independent data

You test whether a new drug increases happiness:

- 100 people receive the drug

- 100 people receive a placebo

- Each person provides one happiness rating (1-7 scale)

- You compare the two groups with a t-test

✓ Independence is reasonable here

Each person contributes exactly one data point.

Another independent example

You test whether people respond differently to metaphor type A vs. B:

- 200 participants, randomly assigned to condition A or B

- Each participant sees one item

- Between-subjects design with one item per person

- Compare responses with OLS regression

✓ Independence is reasonable here

No repeated measures, no item effects to worry about.

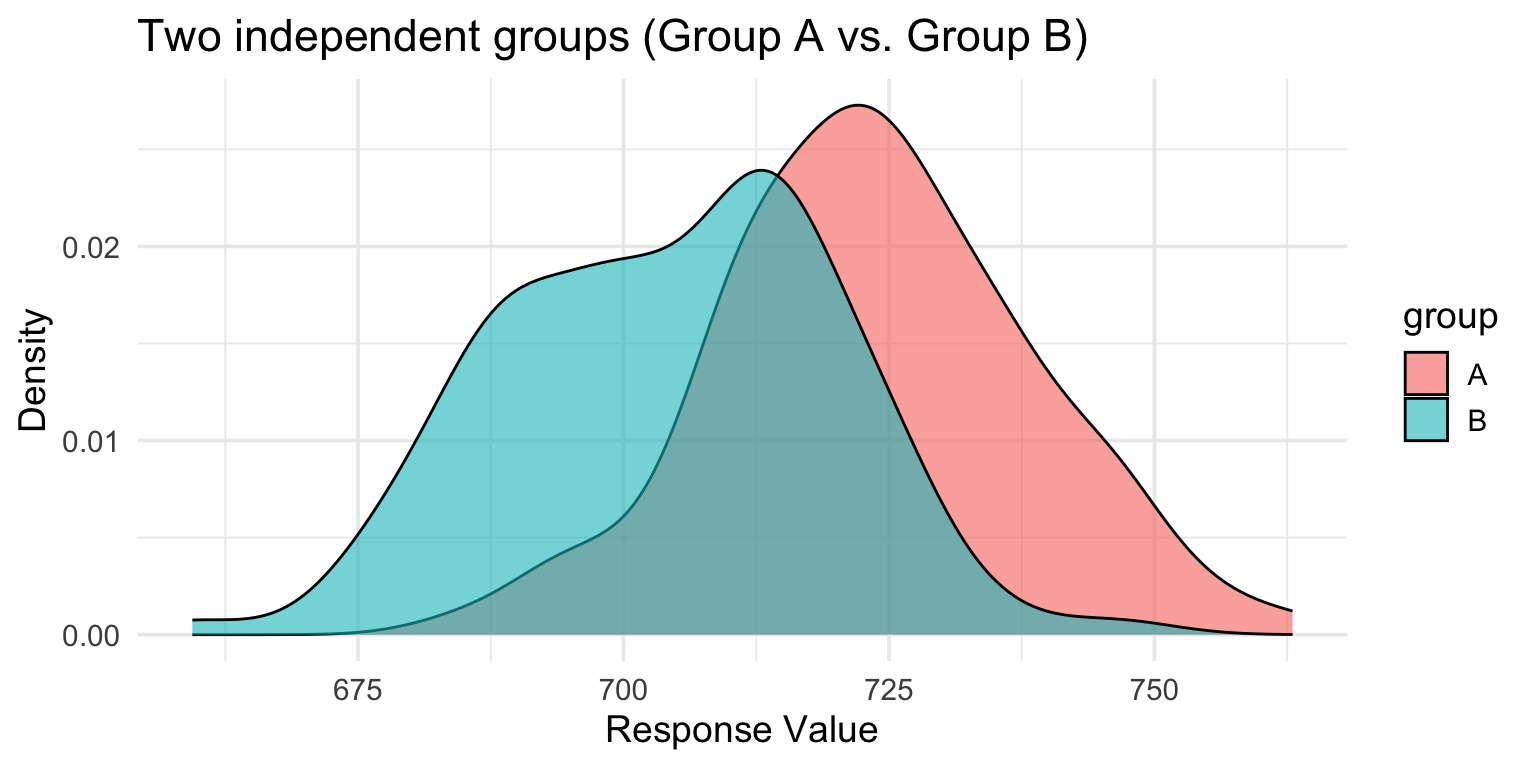

Visualizing independent data

Each observation is independent—no nesting structure.

Analyzing independent data

Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

(Intercept) 725.84046 1.571113 461.991212 3.060339e-302

groupB -20.93401 2.221890 -9.421717 1.194484e-17Interpretation: - Intercept (groupA) = 725.84 (mean of group A) - groupB coefficient = -20.93 (difference from A) - Group B is about 20 units lower than Group A

When independence fails

Non-independence occurs when different observations are systematically related, i.e., they were produced by the same generative process.

Common sources of non-independence in behavioral research:

- Repeated measures: Same participant tested multiple times

- Nested data: Students within classrooms within schools

- Stimulus items: Same stimuli shown to multiple participants

- Time series: Measurements over time from same units

- Clustered designs: Participants recruited from same communities

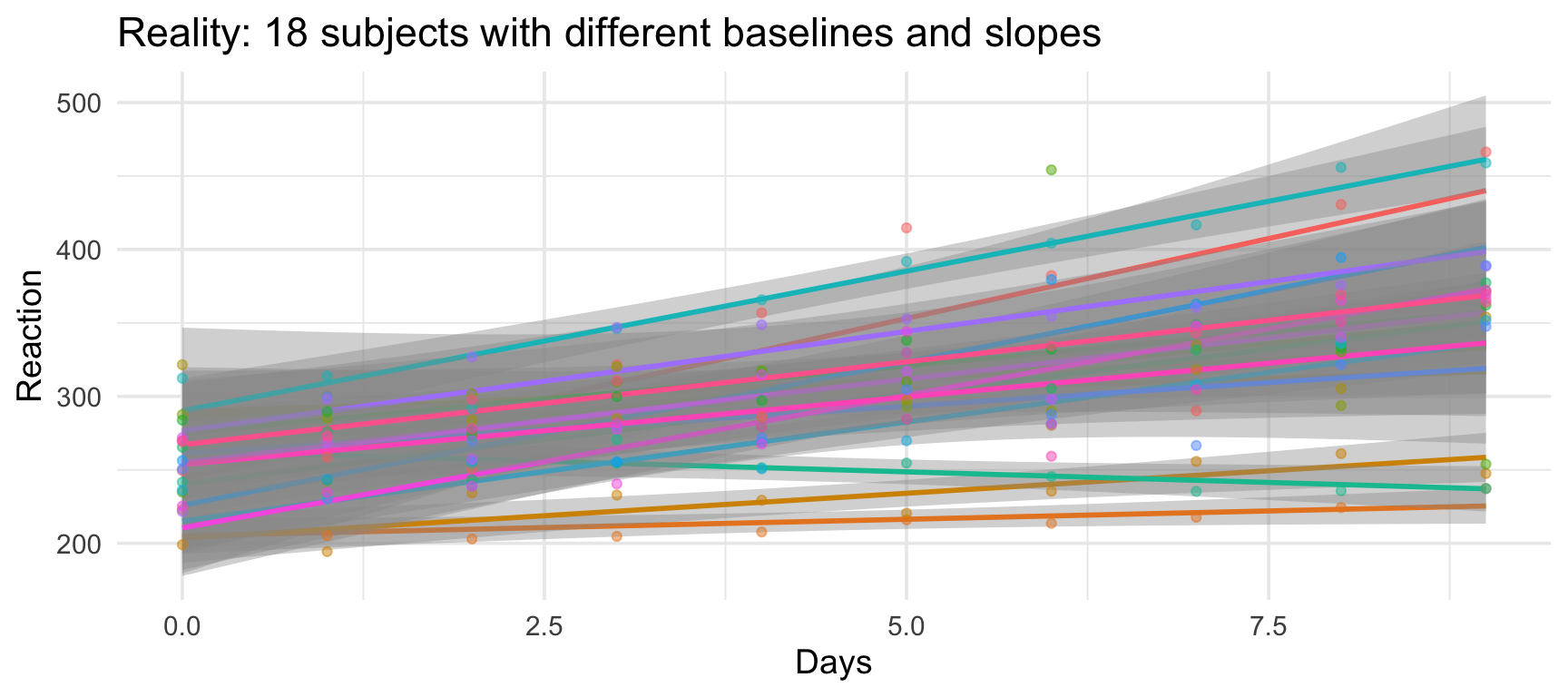

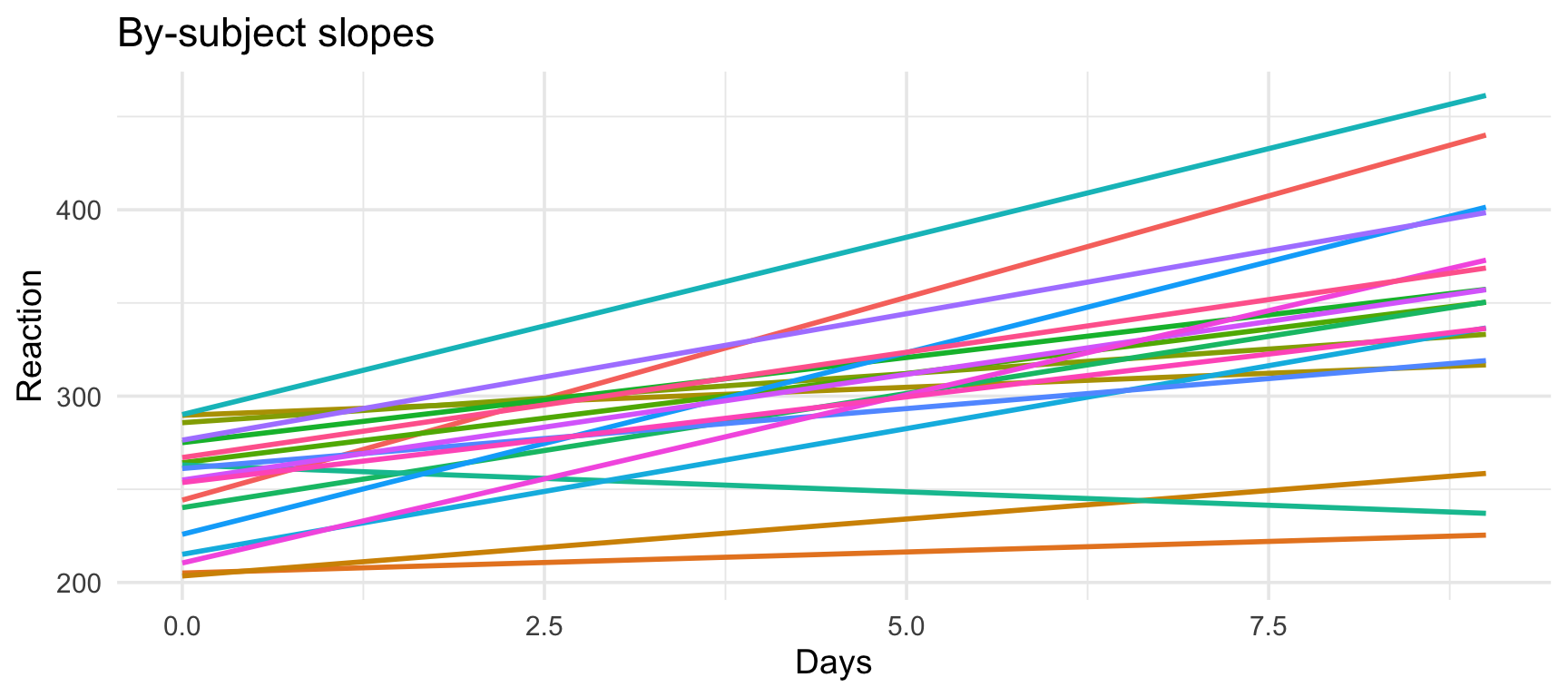

Example: The sleep study

The sleepstudy dataset tracks reaction times in 18 subjects over subsequent days of sleep deprivation:

Reaction Days Subject

1 249.5600 0 308

2 258.7047 1 308

3 250.8006 2 308💭 Check-in

Based on the structure of this study, what might be a source of non-independence?

Naive analysis (wrong!)

Let’s pretend we don’t know about the nested structure:

💭 Check-in

What’s not pictured here?

The real structure

Subjects differ in:

- Overall reaction time (baseline speed)

- Effect of sleep deprivation (some are more resilient)

Subject-level variability

Some subjects are consistently faster; others are consistently slower.

Two types of nested variance

- Random intercepts: Subjects differ in their average reaction time

- Some people are just faster/slower overall

- Even with no sleep deprivation!

- Random slopes: Subjects differ in how much sleep deprivation affects them

- Some people are resilient (shallow slope)

- Others deteriorate quickly (steep slope)

Mixed effects models let us account for both types of variance.

Part 2: Introduction to mixed effects models

Fixed vs. random effects; random intercepts; random slopes.

What are mixed effects models?

Mixed effects models combine:

- Fixed effects: Variables we care about (e.g., experimental conditions)

- These are your hypotheses!

- Estimated with specific coefficient values

- Random effects: Grouping variables that create non-independence

- Sources of variability we need to control for

- Allow intercepts/slopes to vary by group

- Estimated as distributions (variance parameters)

Goal: Get better estimates of fixed effects by accounting for nested structure.

Fixed vs. random effects

Determining which factors to include as fixed vs. random effects is not always straightforward. Here’s a rough guide, but we’ll discuss it again later too:

How do you decide?

- Fixed effects:

- Variables you’re theoretically interested in

- Want to estimate specific coefficient values

- Often experimental manipulations

- Examples: treatment condition, time, drug dosage

- Random effects:

- Grouping/clustering variables

- Want to account for variance, not estimate specific values

- Usually sampling from larger population

- Examples: participant ID, item ID, school, lab

The mixed model formula

Standard regression:

\[Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \epsilon\]

Mixed effects model with random intercepts:

\[Y = (\beta_0 + u_0) + \beta_1 X + \epsilon\]

Where:

- \(\beta_0\) = overall intercept (fixed effect)

- \(u_0\) = subject-specific deviation from overall intercept (random effect)

- \(\beta_1\) = fixed effect of X

- \(\epsilon\) = residual error

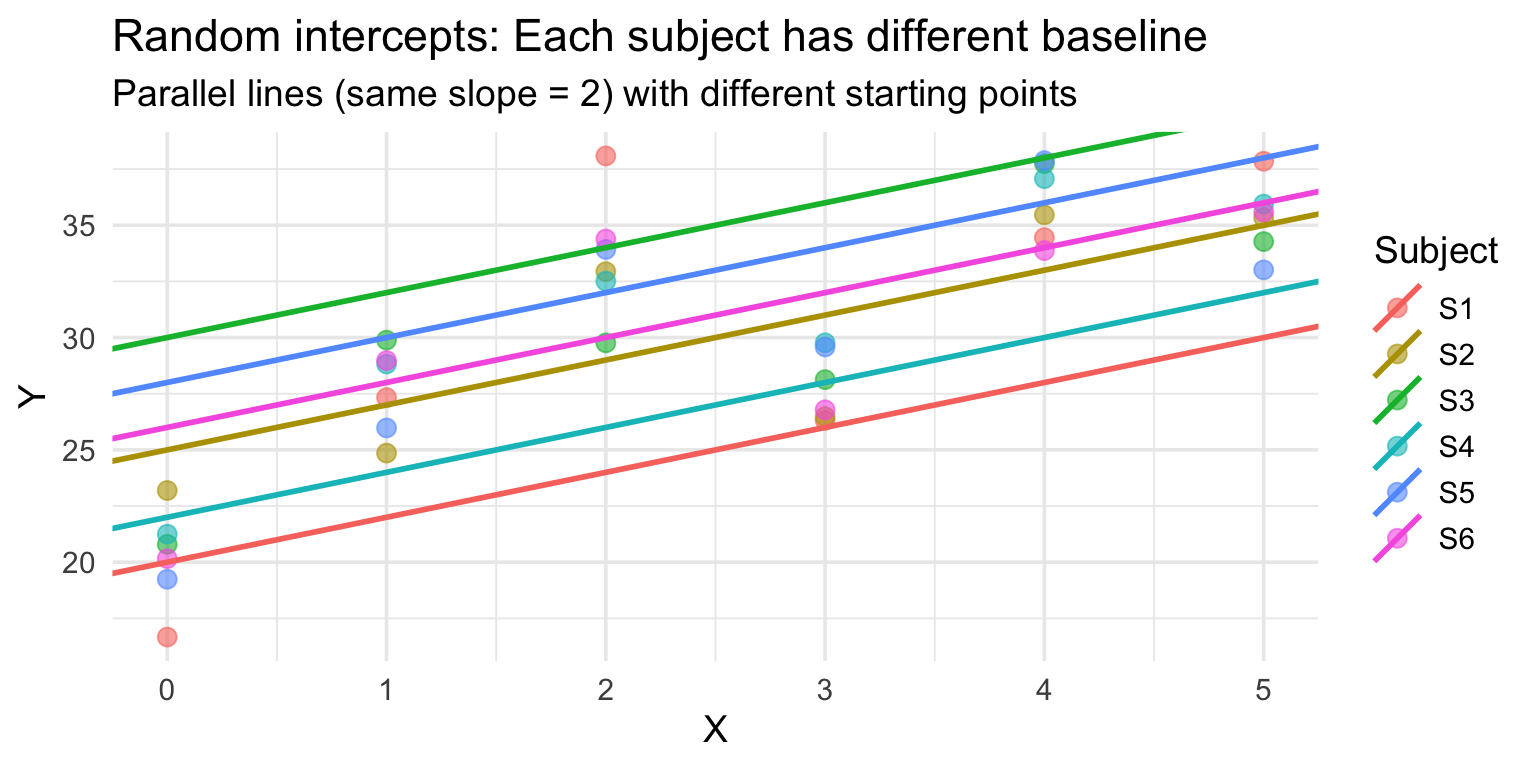

Random intercepts: Intuition

Random intercepts allow each group (e.g., subject) to have its own baseline:

Same slope, different intercepts.

Random intercepts: R syntax

Basic model with random intercepts:

Breaking down the syntax:

Reaction ~ Days: Fixed effect of Days on Reaction(1 | Subject): Random intercept for each Subject1= intercept|= “grouped by”Subject= grouping variable

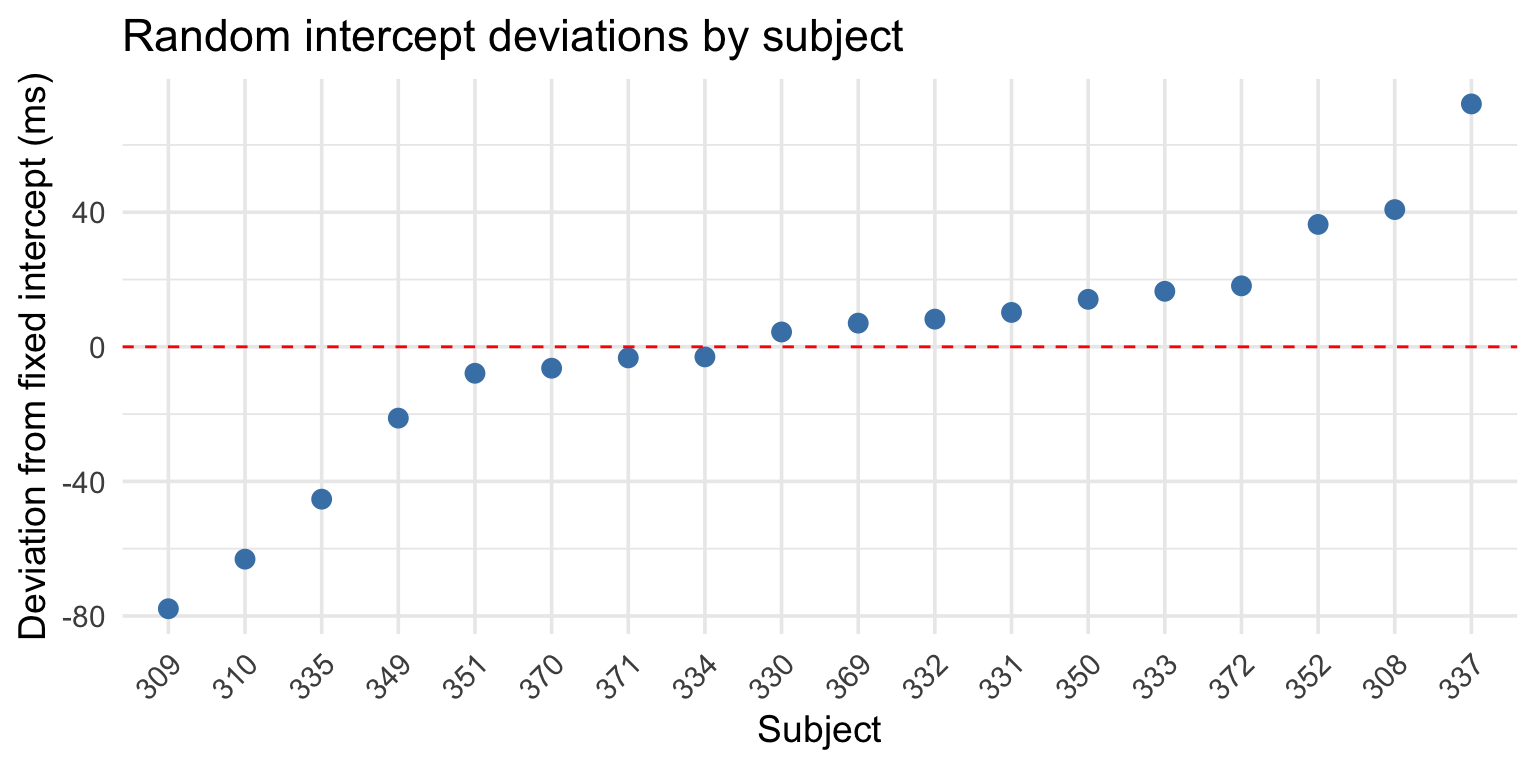

Extracting random intercepts

After fitting the model, you can extract the random effects:

(Intercept)

308 40.783710

309 -77.849554

310 -63.108567

330 4.406442These are deviations from the overall intercept (fixed effect).

Understanding the intercepts

Each subject’s fitted intercept = fixed intercept + random deviation:

(Intercept)

251.4051 [1] 40.78371(Intercept)

292.1888 Visualizing random intercepts

Random slopes: Intuition

Random slopes allow the effect of X to vary by group:

Random slopes: R syntax

Model with random intercepts AND slopes:

Estimate Std. Error t value

(Intercept) 251.40510 6.824597 36.838090

Days 10.46729 1.545790 6.771481Breaking down the syntax:

Reaction ~ Days: Fixed effect of Days(1 + Days | Subject): Random effects for Subject1= random interceptDays= random slope for Days|= grouped bySubject= grouping variable

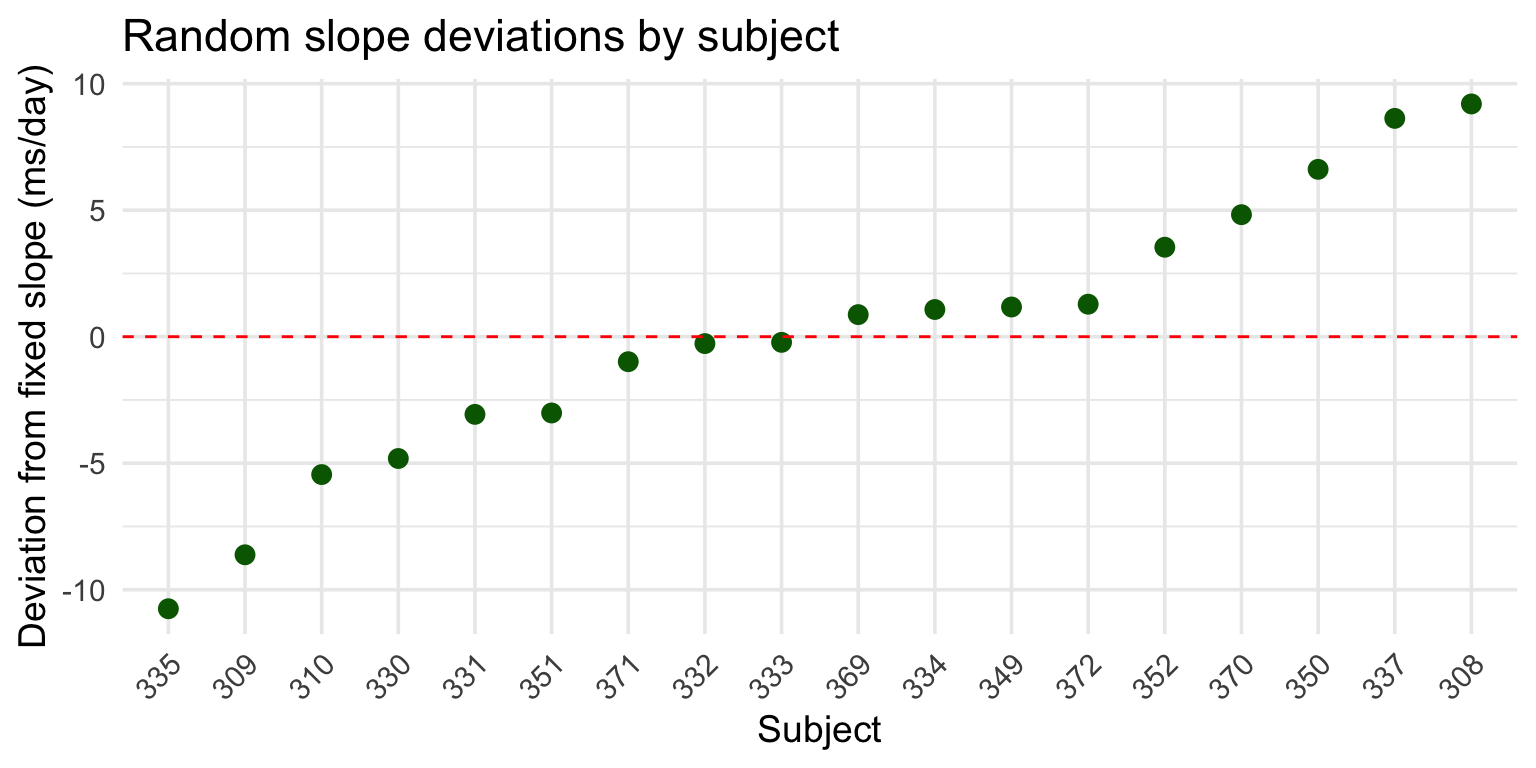

Extracting random slopes

After fitting the model, you can extract the random effects:

(Intercept) Days

308 2.258551 9.198976

309 -40.398738 -8.619681

310 -38.960409 -5.448856

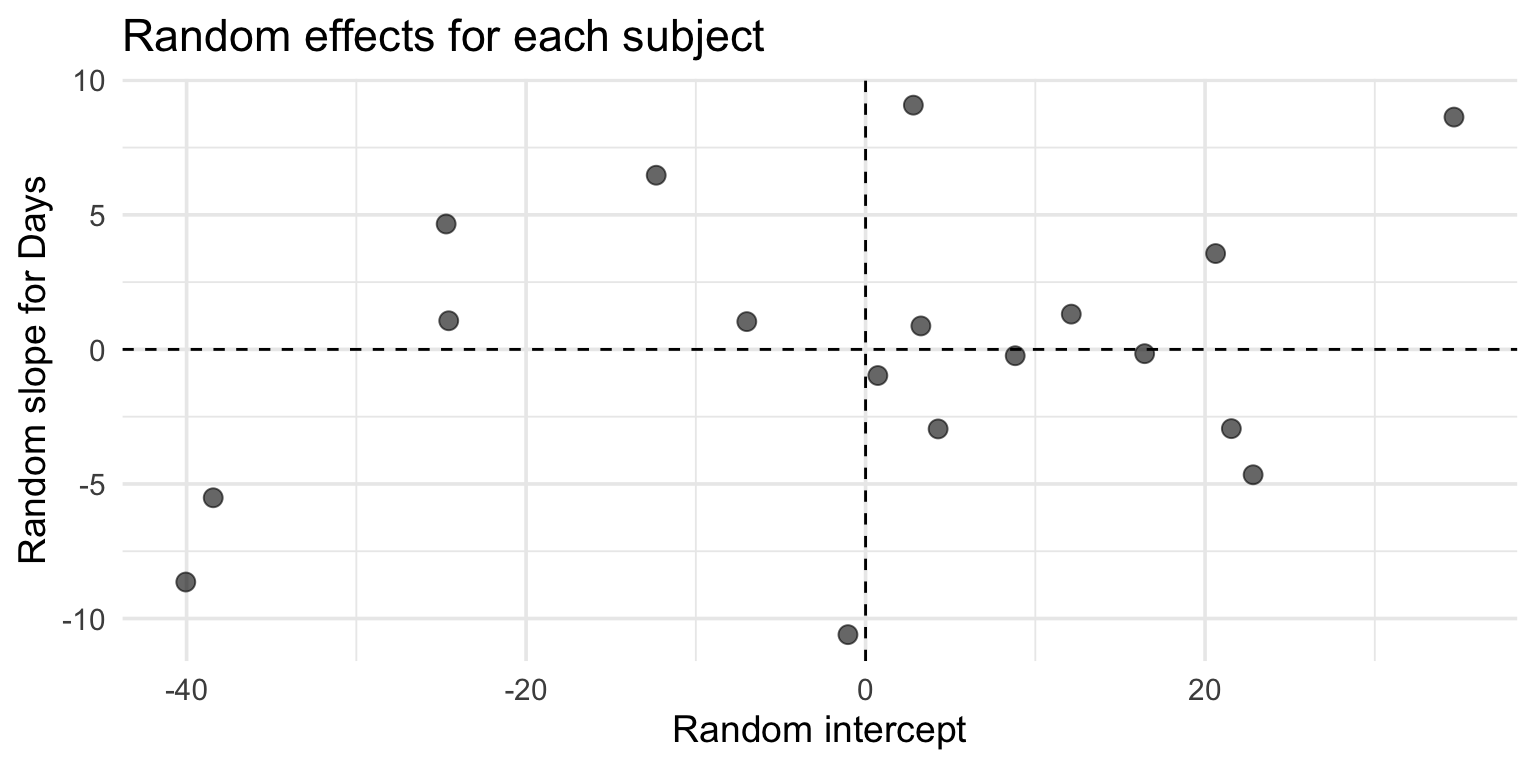

330 23.690620 -4.814350Now, we have deviations from the intercept and from the Days slope.

Understanding the slopes

Each subject’s fitted slope = fixed slope + random deviation:

Days

10.46729 [1] 9.198976 Days

19.66626 Subject 308’s RT increases by ~19.67 ms per day (vs. population average of ~10.47 ms).

Visualizing random slopes

Why random slopes matter

Without random slopes: - Assumes the effect is the same for everyone - Underestimates uncertainty in the fixed effect - Can lead to false positives

With random slopes: - Acknowledges that effects vary across individuals - Provides more conservative (realistic) estimates - Better generalization to new subjects

Rule of thumb: If a variable varies within your grouping variable, include it as a random slope.

Multiple random effects

You can include multiple sources of random effects:

Common in psycholinguistics: - Random effects for subjects (people vary) - Random effects for items (stimuli vary) - Called “crossed random effects”

Conceptual summary

Mixed effects models help when:

- You have repeated measures

- You have nested/hierarchical structure

- You want to generalize beyond your specific sample

Key components:.

- Fixed effects: Your hypotheses.

- Random intercepts: Group-level baseline differences

- Random slopes: Group-level differences in effects.

Part 3: Using lme4

Building and evaluating models; model comparisons; best practices and common issues.

The lme4 package

Most common R package for mixed models:

Main functions: - lmer(): Linear mixed effects models - glmer(): Generalized linear mixed models (logistic, Poisson, etc.)

Building your first model

Let’s fit a model with random intercepts only:

Note: REML = FALSE uses maximum likelihood estimation, which we need for model comparison.

Viewing model output

Linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood ['lmerMod']

Formula: Reaction ~ Days + (1 | Subject)

Data: sleepstudy

AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) df.resid

1802.1 1814.9 -897.0 1794.1 176

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.2347 -0.5544 0.0155 0.5257 4.2648

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

Subject (Intercept) 1296.9 36.01

Residual 954.5 30.90

Number of obs: 180, groups: Subject, 18

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error t value

(Intercept) 251.4051 9.5062 26.45

Days 10.4673 0.8017 13.06

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

Days -0.380Adding random slopes

Now let’s add random slopes for the Days effect:

This allows both the intercept AND the slope to vary by subject.

Comparing the models

Linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood ['lmerMod']

Formula: Reaction ~ Days + (1 + Days | Subject)

Data: sleepstudy

AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) df.resid

1763.9 1783.1 -876.0 1751.9 174

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-3.9416 -0.4656 0.0289 0.4636 5.1793

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev. Corr

Subject (Intercept) 565.48 23.780

Days 32.68 5.717 0.08

Residual 654.95 25.592

Number of obs: 180, groups: Subject, 18

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error t value

(Intercept) 251.405 6.632 37.907

Days 10.467 1.502 6.968

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

Days -0.138Model comparison: The logic

The likelihood of a model refers to the probability of the observed data under that model’s parameter estimates.

Question: Does adding variable \(X\) improve the model over a model without \(X\)?

Approach: Likelihood ratio test (LRT)

- Compare log-likelihood of two nested models

- Model with more parameters should fit better

- But: is the improvement “worth it”?

- Test statistic: \(\chi^2 = -2(LL_{reduced} - LL_{full})\)

- Compare to chi-square distribution (Wilk’s Theorem).

Running model comparison

Data: sleepstudy

Models:

model_reduced: Reaction ~ (1 + Days | Subject)

model_full: Reaction ~ Days + (1 + Days | Subject)

npar AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) Chisq Df Pr(>Chisq)

model_reduced 5 1785.5 1801.4 -887.74 1775.5

model_full 6 1763.9 1783.1 -875.97 1751.9 23.537 1 1.226e-06 ***

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1Interpretation:: Adding Days significantly improves fit

Extracting coefficients

Fixed effects (population-level):

(Intercept) Days

251.40510 10.46729 Random effects (subject-specific deviations):

(Intercept) Days

308 2.815789 9.075507

309 -40.047855 -8.644152

310 -38.432497 -5.513471

330 22.831765 -4.658665Visualizing random effects

Generalized linear mixed models

A generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) is a general framework for fitting regression models with various link functions (e.g., logit) and random effects.

- We’ve already discussed GLMs (

glm) and logistic regression. - A GLMM is just a way to add random effects structure to a GLM.

glmeris toglmaslmeris tolm.

Example: Binary outcomes

Scenario: Testing accuracy on a memory task

- Each participant completes multiple trials

- Each trial is coded as correct (1) or incorrect (0)

- We want to know if reaction time predicts accuracy

Subject Trial RT Correct

1 1 1 443.9524 0

2 2 1 476.9823 0

3 3 1 655.8708 0

4 4 1 507.0508 0Naive approach (wrong!)

What if we use regular logistic regression?

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -4.333121392 1.267280721 -3.4192277 0.0006279914

RT 0.001789766 0.002405329 0.7440834 0.4568259948Problem: This ignores that we have 30 trials per subject! Standard errors will be too small.

Using glmer()

Add random effects for subjects:

Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

Approximation) [glmerMod]

Family: binomial ( logit )

Formula: Correct ~ RT + (1 | Subject)

Data: binary_data

AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) df.resid

174.0 187.2 -84.0 168.0 597

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.2395 -0.1897 -0.1784 -0.1685 6.4595

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

Subject (Intercept) 0 0

Number of obs: 600, groups: Subject, 20

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -4.333121 1.277856 -3.391 0.000697 ***

RT 0.001790 0.002425 0.738 0.460513

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

RT -0.983

optimizer (Nelder_Mead) convergence code: 0 (OK)

boundary (singular) fit: see help('isSingular')Syntax breakdown: - Correct ~ RT: Fixed effect of RT on accuracy - (1 | Subject): Random intercept for each subject - family = binomial(link = "logit"): Logistic regression

Interpreting GLMM output

Generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood (Laplace

Approximation) [glmerMod]

Family: binomial ( logit )

Formula: Correct ~ RT + (1 | Subject)

Data: binary_data

AIC BIC logLik -2*log(L) df.resid

174.0 187.2 -84.0 168.0 597

Scaled residuals:

Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

-0.2395 -0.1897 -0.1784 -0.1685 6.4595

Random effects:

Groups Name Variance Std.Dev.

Subject (Intercept) 0 0

Number of obs: 600, groups: Subject, 20

Fixed effects:

Estimate Std. Error z value Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) -4.333121 1.277856 -3.391 0.000697 ***

RT 0.001790 0.002425 0.738 0.460513

---

Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

Correlation of Fixed Effects:

(Intr)

RT -0.983

optimizer (Nelder_Mead) convergence code: 0 (OK)

boundary (singular) fit: see help('isSingular')Example: Binary outcomes

Scenario: Testing accuracy on a memory task

- Each participant completes multiple trials

- Each trial is coded as correct (1) or incorrect (0)

- We want to know if reaction time predicts accuracy

Part 4: Best practices

Choosing random effects; dealing with convergence warnings; reporting results.

Common questions

Mixed effects models can get complex pretty quickly. Researchers end up running into a number of common questions:

- Which effects should be random and which should be fixed?

- How many random effects should I specify? Just random intercepts? Random slopes?

- What happens if my model doesn’t “converge”?

- How do I report my results?

We’ll tackle each of these one by one.

Fixed vs. random?

Selecting fixed vs. random effects can be challenging. There’s not even universal consensus on the best way to do this!

Some ways to think about it:

- In terms of sampling: Fixed effects exhaust the theoretical population (e.g., condition 1 vs. condition 2), and random effects are just a sample (e.g., of participants).

- In terms of estimation process: Fixed effects are estimated using maximum likelihood estimation, and random effects are estimated with shrinkage.

- In terms of interest: Fixed effects are what you’re interested in, and random effects are what you want to control for.

How many random effects to include? (1)

Barr et al. (2013): “Keep it maximal”

- Include the most complex random effects structure justified by your design

- Include random slopes for within-unit variables

- This reduces Type I error and improves generalizability

Example:

How many random effects to include? (2)

Bates et al. (2015): “Parsimonious mixed models”

- Maximal models often fail to converge or produce singular fits (coming up!)

- Start with maximal model, then simplify if necessary

- Remove random effect correlations first, then non-significant random slopes

- Balance between Type I error control and model stability

Example:

When maximal models fail

Common issues:

- Convergence failures: Model can’t find solution

- Singular fit: Some variance is estimated as zero

- Computational issues: Model is too complex for data

Dealing with convergence issues

Step 1: Check your data - Are there enough observations per group? - Any extreme outliers?

Step 2: Rescale continuous predictors

Step 3: Try different optimizer

Simplifying random effects

Step 4: Simplify random effects structure

Start by removing correlations between random effects:

Step 5: Remove random slopes if necessary

Use model comparison to determine which random effects are necessary (Bates et al., 2015).

Reporting your results

Template for reporting:

We fit a linear mixed effects model predicting reaction time from days of sleep deprivation. The model included random intercepts and random slopes for days grouped by subject. Sleep deprivation significantly increased reaction time (β = 10.47, SE = 1.55), with each additional day of deprivation associated with an ~10.5 ms increase in RT. A likelihood ratio test confirmed that including days as a fixed effect significantly improved model fit, χ²(1) = 45.85, p < 0.001.

What to report

Essential information:

- Random effects structure (what’s included)

- Fixed effect estimates (β, SE, or CI)

- Test statistic and p-value (LRT)

- Model comparison details (which models, df, χ²)

- Software and package versions

Key papers:

- Barr et al. (2013): Keep it maximal

- Bates et al. (2015): Parsimonious mixed models

- Winter (2013): Linear mixed effects models in R

Tutorials:

- This lecture!

- Bodo Winter’s tutorial

- Michael Clark on shrinkage

Documentation:

lme4package documentation- Hierarchical models visualization

Conclusion

- Mixed models are a valuable tool for modeling non-independent data.

- Random intercetps model correlated variance in

y; random slopes model correlated variance iny ~ x. - Coming up, we’ll discuss:

- More complex models (e.g., nested variance).

- Deep dive into fitting random effects (e.g., pooling).

- Understanding the outputs (e.g., variance partitioning).

- Best practices (e.g., “keep it maximal”).

- Diagnozing and fixing common issues (e.g., convergence failures).

- Generalizing to generalized linear mixed effects models.

CSS 211 | UC San Diego